I have been thinking, lately, about how despite all the inner work one does, the battle with the limited self must continue throughout life. Presumably, this is because what we call the “ego” or the “nafs” (in Sufi terminology) is necessary to our experience on the earth plane. As I understand it, it works as a sort of anchor to hold us to this plane of materiality, and the overcoming of its limitations seems to be the primary vehicle for learning what we come here to learn. The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon Him, said in a Hadith that the human being is actually higher than the angels, because in coming here for the earth experience, the soul has the opportunity to actualize the God-self, while the angels remain caught in contemplation of God. The descent of the soul out of the unity of divine Being into humanity is the ultimate descent, its limitation being symbolized by the crucifixion of Christ.

Inayat Khan, in The Unity of Religious Ideals, illuminates the battle with the limited self by telling the story of Krishna and Arjuna in the Bhagavad-Gita, which metaphorically describes the inner battle with the limited self in the war that Arjuna must fight. In his fear and anguish, caught between two sides, he consults his charioteer, Krishna, and gradually Krishna helps him to see what the battle really means, and how to win it. It is a good way to describe the battle of the soul with the ego, because in reality, the inner battle can only be fought through outer circumstances. Inayat Khan writes:

. . . the latter part of Krishna’s life has two very important aspects. One aspect teaches us that life is a continual battle and the earth is the battlefield where every soul has to struggle, and the one who wants to own the kingdom of the earth must be well acquainted with the law of warfare. S/He must learn the secret of an offensive, the mystery of defense, how to hold her or his position, how to retreat, how to advance, and how to change position; how to protect and control all that has been won, how to abandon that which must be given up, the manner of sending an ultimatum, the way of making an armistice, and the method by which peace is made. In the battle of life man’s position is most difficult. S/He has to fight on two fronts at the same time: one enemy is himself, and the other is before him. If s/he is successful on one front and fails on the other front, then his or her success is not complete. (Inayat Khan, Volume IX, The Unity of Religious Ideals)

A well-known aphorism comes to mind here: Choose your battles, as the saying goes. Recently, I found myself in conflict with some colleagues, and this whole idea was brought home to me quite thoroughly: those colleagues got the jump on me in a situation where they ought to have shown more ethical and professional discretion, and I found myself powerless to do much of anything about it when I realized what had happened. How to deal with this, I wondered, and as someone with a strong inner life, I was frustrated to find myself ready to “spit nails.” On an outer level, I did what I could do: there were three people with whom I found myself in this situation, and one of them was fairly innocent, because he was on the outside and was used to accomplish the ends of the other two. Another of these colleagues was someone I had long ago realized was going to do what she would do without any thought for ethical protocol or what the Sufis call adab, or fineness of manner. Such a person cannot be fought, except within. More on that later. The third of these people was someone who is mostly just a bit inexperienced, and was probably just thoughtless in this situation. In pain and suffering, I confronted her, as wisely and compassionately as I could, and endured her rage, remembering that I was once exactly where she was, and knowing that she would eventually grow through her hypersensitivity.

But the one in the middle, the one who had proven herself unbeatable without resorting to her own machinations in order to “win.” What about her? Vanquishing an enemy such as this is fairly impossible in outer circumstances, because one demeans oneself if one resorts to the tactics the other person is willing to use in order to attain her ends. Thus, it occurred to me that first, I needed to look inside to find out why this person had such power over me. The answer came immediately, in identifying the bodily sensations that arose at the thought of this person’s treachery: I realized that she invoked the fear and powerlessness that came over me as a small child with an older sibling who later was revealed to have clear antisocial tendencies, and who tormented me, as the “baby of the family,” throughout my childhood. This kind of family dynamic is fairly common in dysfunctional, alcoholic families, as mine was; and while I would like to say I overcame my fear and frustration, I think that in the continued appearance of similar people in my life, I still have a ways to go. So there I am: Arjuna on the battlefield of the soul.

What is to be done when one cannot fight outwardly without making a fool of oneself, to say nothing of making public one’s fear and frustration? How do we deal with behavior it would demean us to even recognize, let alone fight?

The battle of each individual has a different character; it depends upon a man’s particular grade of evolution. Therefore every person’s battle in life is different, and of a peculiar character. No one in the world is exempt from that battle; only, one is more prepared for it while the other is perhaps ignorant of the law of warfare. And in the success of this battle lies the fulfillment of life. The Bhagavad-Gita, the Song Celestial, from the beginning to end is a teaching on the law of life’s warfare. (Inayat Khan)

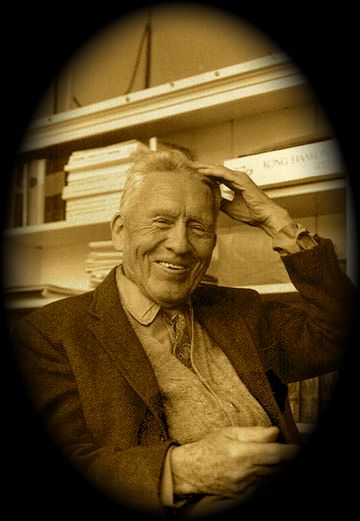

When Inayat Khan came to the West, an Indian in what was then a very strange and alien culture, he came with a purpose: to spread the Message of the unity of all religions, to teach his own understanding of Sufism, a philosophy that superceded differences and distinctions, one that went beyond dogmas, theologies and philosophies: simply, love, harmony and beauty. To those who met him, he seemed to be a simply astounding presence, the true embodiment of spiritual realization. Yet in a sense, he was somewhat of an innocent in the culture of a war-torn Europe. It didn’t take long for a sizeable group of students to be attracted to him and his Message, but they were very human beings, and the constant battle of politics and personalities became more and more discouraging to him. One of my life’s teachers, Shamcher (one of his early students) said to me that “the Sufi has two points of view: his own and that of the other.” Murshid (the name his students called Inayat Khan, meaning “teacher”) was beset on either side with students complaining about other students, power battles, battles with the outer world, constant poverty while he tried to do his spiritual work and still support his family; at one point, when a student kept coming to complain about another, he simply said, “Well, that’s what he did today. Let us see what he will do tomorrow.” How does such a being–or any being–maintain equanimity in the face of this kind of constant negativity? And the battles continue today, as they seem to in every church, spiritual and secular organization, all of which seem to exist in order to facilitate opportunities for the soul to fight its battle with its ego. Shamcher humorously said, “God wanted to create Hell, so he created the committee.”

Arjuna speaks:

Drive my chariot, Krishna immortal, and place it between the two armies.

That I may see those warriors who stand there eager for battle, with whom I must now fight at the beginning of this war.

That I may see those who have come here eager and ready to fight, in their desire to do the will of the evil son of Dhrita-Rashtra. (From the Bhagavad Gita)

If you are reading this and it evokes similar situations you have had to fight, and you are hoping I am going to offer you some solution, I hate to disappoint you, because I don’t have any easy solutions for you. I fight this battle every day of my life, and I have come to realize that I am not alone in this battle.

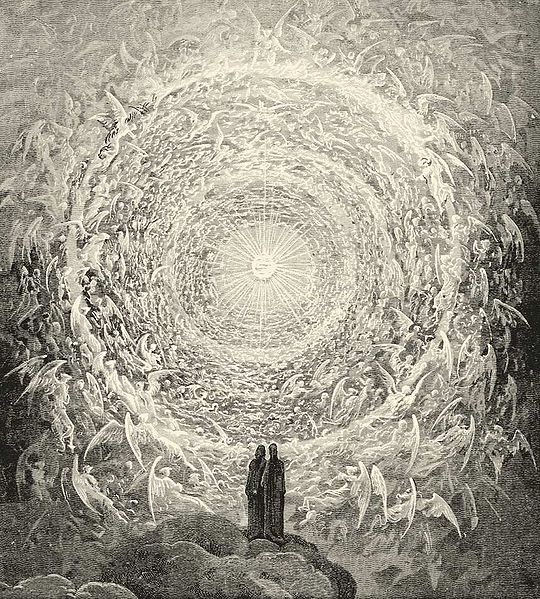

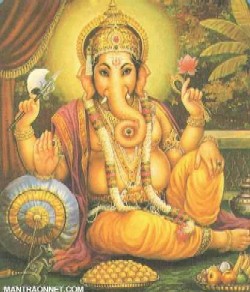

Krishna, of course, represents the God-ideal, and it is God who is both sides of the battle, the war, and Arjuna. It strikes me, here, that the important idea in this brief verse is in seeing: put me in the middle, the passage says. Let me see both sides equally, both good and bad. Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, the son and successor of Inayat Khan, often told his students, of which I am one, that we ought not just learn to see with the eyes of God, but to BECOME the divine glance. How else do we learn to fight if we cannot not only see, but become that Glance? While I–or you–may need to become aware of my personal issues, the impressions I have retained in the battle of life, the wounds that have not yet completely healed, the “ego-trips” I put myself through, it seems to me that I cannot win my battles–or my ultimate Battle–until I learn to see the entire battlefield with the eyes of God.

When Krishna heard the words of Arjuna he drove their glorious chariot and placed it between the two armies.

And facing Bhishma and Drona and other royal rulers he said: ‘See, Arjuna, the armies of the Kurus, gathered here on this field of battle.’

Then Arjuna saw in both armies fathers, grandfathers, sons, grandsons; fathers of wives, uncles, masters; brothers, companions and friends.

When Arjuna thus saw his kinsmen face to face in both lines of battle, he was overcome by grief and despair, and thus he spoke with a sinking heart. (Bhagavad Gita)

Arjuna is overcome with despair: Lord Krishna has enabled him to see through His eyes, and he now sees both sides. How can he fight? How can he take sides? He weeps at the idea of killing anyone, because no one is an enemy, they are all parts of himself. Lord Krishna,however, lets him see that on this occasion, the fight must be fought, and that on another level, it makes sense to fight it, and it is okay to fight. There is a reality beyond the apparent battle:

Krishna speaks:

Thy tears are for those beyond tears; and are they words words of wisdom? The wise grieve not for those who live; and they grieve not for those who die; for life and death shall pass away.

Because we all have been for all time: I, and thou, and these kings of men. And we all shall be for all time, we all for ever and ever. (Bhagavad Gita)

Arjuna is catapulted beyond the apparent and into the real. He sees that, whatever this battle is about, there is a greater reality that is beyond it that must be kept in mind if he is to win. He sees beyond the veil, from the apparent to the real. Then why is the battle taking place? And why must it be won? Must it even be fought?

Many people today ask why, if there is a God, should wars and disasters take place. And many give up their belief when they think more about it. The image of Krishna with a sword, going to war, shows that God who is in heaven, and who is most kind, is yet the same God who stands with a sword in his hand; that there is no name, no form, no place, no occupation, which is devoid of God. It is a lesson that we should recognize God in all, instead of limiting Him only to the good and keeping Him away from what we call evil; for this contradicts the saying: ‘In God we live and move and have our being.’ (Inayat Khan)

Rumi said,”If I told what I knew, the world would be in flames.” How do we know what is transpiring beyond that which occurs? How do we get beyond the petty grievances and frustrations, the battles of everyday living? By learning to see. It seems to this person that no matter what we call our ideal, whether to us it is a God ideal or an idea or a concept or a theology or philosophy, it is is truly our own, it will lead us to reality. In time, we learn to see which battles must be fought and which must be given up. We see who the enemy really is, and we learn to see ourselves in that enemy. Gandhi said that we can only win over our enemy if we love her or him more than ourselves.

There is always more work to do.

We succeeded in getting away to the beach for a few days this week, something that doesn’t happen nearly as often as I’d like, given our different schedules. Here where we live in the Piedmont of North Carolina, we are not actually very far from the ocean: three to five hours at most, depending on where one goes on this Graveyard of the Atlantic shoreline. This time, given our lack of time, we went to Topsail Island, which bills itself, these days, as being on the Outer Banks, an inclusion I do not recall from the days when my family-of-origin went yearly to the “real” Outer Banks, where we had a cottage, one of those funky little flat-roofed-cinder-block-post-modern affairs that had no modern conveniences whatsoever, even for those times. I loved it. My family-of-origin was a perpetually stressed and miserable group of people, and those summers at the beach were my healing from each winter of cold rage and cabin fever in the mountain town where we lived. My kinship with the ocean remains to this day, although it has become an internalized seascape that makes theses trips less necessary than before, a seascape that is far more perfect and creatively changeable than those landscapes I was exposed to throughout my life, the ones that began that internalization process. I have tried to live on or near the sea most of my life: our family has lived in such places as Cape Cod, Chesapeake Bay, and even on Lake Superior, which was a great lesson to me in terms of the archetypal “inland sea.” We lived, for two years, in an Aleut fishing village on the Alaskan Peninsula, too, in a cove off the Pacific Ocean, and that, of course, was the most amazingly beautiful and stark landscape I have ever loved and been daily overwhelmed by. Topsail Beach, with it’s overbuilt series of coastal towns and ticky-tacky houses built within such proximity to each other that residents could have little real privacy, with its mom-and-pop restauratns and dives, and its overall honky-tonk atmosphere, is a poor comparison; but my beloved ocean continues to resist all attempts to turn her into an offshoot of such desecrations of her shores, although those are sorrowful enough… Yet even then, the winds and the sand, the weather that brooks no denial, and the constant change wrought by all these continues to hold a mystical pull on those who walk her beaches, whether they do so with a beer can in their hands, a surfboard or a pail and shovel, running shoes on their feet. . . or whether, as I did, they huddle in a beach chair wrapped up against the cold and intone sacred sounds that weave their way in and out of the howling winds and the constant pounding of the surf. There is something about proximity to the sea that is an ongoing mystic pull toward the absolute loneliness of God. Perhaps there is no difference.

We succeeded in getting away to the beach for a few days this week, something that doesn’t happen nearly as often as I’d like, given our different schedules. Here where we live in the Piedmont of North Carolina, we are not actually very far from the ocean: three to five hours at most, depending on where one goes on this Graveyard of the Atlantic shoreline. This time, given our lack of time, we went to Topsail Island, which bills itself, these days, as being on the Outer Banks, an inclusion I do not recall from the days when my family-of-origin went yearly to the “real” Outer Banks, where we had a cottage, one of those funky little flat-roofed-cinder-block-post-modern affairs that had no modern conveniences whatsoever, even for those times. I loved it. My family-of-origin was a perpetually stressed and miserable group of people, and those summers at the beach were my healing from each winter of cold rage and cabin fever in the mountain town where we lived. My kinship with the ocean remains to this day, although it has become an internalized seascape that makes theses trips less necessary than before, a seascape that is far more perfect and creatively changeable than those landscapes I was exposed to throughout my life, the ones that began that internalization process. I have tried to live on or near the sea most of my life: our family has lived in such places as Cape Cod, Chesapeake Bay, and even on Lake Superior, which was a great lesson to me in terms of the archetypal “inland sea.” We lived, for two years, in an Aleut fishing village on the Alaskan Peninsula, too, in a cove off the Pacific Ocean, and that, of course, was the most amazingly beautiful and stark landscape I have ever loved and been daily overwhelmed by. Topsail Beach, with it’s overbuilt series of coastal towns and ticky-tacky houses built within such proximity to each other that residents could have little real privacy, with its mom-and-pop restauratns and dives, and its overall honky-tonk atmosphere, is a poor comparison; but my beloved ocean continues to resist all attempts to turn her into an offshoot of such desecrations of her shores, although those are sorrowful enough… Yet even then, the winds and the sand, the weather that brooks no denial, and the constant change wrought by all these continues to hold a mystical pull on those who walk her beaches, whether they do so with a beer can in their hands, a surfboard or a pail and shovel, running shoes on their feet. . . or whether, as I did, they huddle in a beach chair wrapped up against the cold and intone sacred sounds that weave their way in and out of the howling winds and the constant pounding of the surf. There is something about proximity to the sea that is an ongoing mystic pull toward the absolute loneliness of God. Perhaps there is no difference. the little girls and boys and their mothers playing joyfully in the surf, while the men of the group stood around on the beach with their shoes still on, seeming to show little interest in that seascape of seascapes, perhaps discussing the manly things men usually discuss. We lived in Amish and Mennonite environs at several points in our lives, and we were aware that these are a very private people who do not like to have their pictures taken and would be highly unlikely to put on bathing suits and actually get into the water, even if it were not still too cold to. But the women and children, wearing their lovely, long cotten dresses with Peter Pan collars, their bonnet strings dangling, made a lovely work of art there in the surf, leaning into the wind and the the inexorable crashing waves. We couldn’t resist a few surreptitious pictures, and hope that we have not intruded too much on their privacy by putting them up here.

the little girls and boys and their mothers playing joyfully in the surf, while the men of the group stood around on the beach with their shoes still on, seeming to show little interest in that seascape of seascapes, perhaps discussing the manly things men usually discuss. We lived in Amish and Mennonite environs at several points in our lives, and we were aware that these are a very private people who do not like to have their pictures taken and would be highly unlikely to put on bathing suits and actually get into the water, even if it were not still too cold to. But the women and children, wearing their lovely, long cotten dresses with Peter Pan collars, their bonnet strings dangling, made a lovely work of art there in the surf, leaning into the wind and the the inexorable crashing waves. We couldn’t resist a few surreptitious pictures, and hope that we have not intruded too much on their privacy by putting them up here.  What an endless variety of life lives itself in the least expected places! God is constantly writing in one book or another, and we were delighted with this particular one.

What an endless variety of life lives itself in the least expected places! God is constantly writing in one book or another, and we were delighted with this particular one. draped with various memorabilia, reminded me of those leaning at intervals on the dunes of the Bering Sea where I used to go to work monthly up in Alaska: cross after cross in memory of those who had lost their life at sea. We come and we go.

draped with various memorabilia, reminded me of those leaning at intervals on the dunes of the Bering Sea where I used to go to work monthly up in Alaska: cross after cross in memory of those who had lost their life at sea. We come and we go.